Leonardo Bigollo (Leonardo Pisano or de Pisa) was a mathematician who

lived in Italy between the 12th and 13th century (1170-1240) and who turned

to turn his back on the Roman numerals system that prevailed at that time.

He has been known throughout history by his nickname: Fibonacci, a derivative

of adding the words fillius + bonnacci which, in Latin and Italian mean something

along the lines of “son of the well intended”. Apparently, Fibonacci’s father

(Guglielmo) was a good person, as well as being a trader, travelling through

North Africa. It was there that his son Leonardo discovered the magic of

Arabic numbers.

The Hindu Arabic system traveled from India to Persia and then on to the

Middle East and Northern Africa, from where it jumped to Europe thanks to,

among other mathematicians, Fibonacci.

The Pisan’s idea of using Arabic numbers included the possibility of working with

whole numbers or fractions, dividing a number into prime factors, square roots, etc.

It wasn’t easy to adopt this system despite its numerous advantages.

The Crusades against Islam that were ongoing at the time placed anything

labeled as “Arabic” under suspicion.

Arabic numbers were even banned in the city of Florence in 1299 on the grounds

that “they were easier to falsify than Roman numerals”.

Middle East and Northern Africa, from where it jumped to Europe thanks to,

among other mathematicians, Fibonacci.

The Pisan’s idea of using Arabic numbers included the possibility of working with

whole numbers or fractions, dividing a number into prime factors, square roots, etc.

It wasn’t easy to adopt this system despite its numerous advantages.

The Crusades against Islam that were ongoing at the time placed anything

labeled as “Arabic” under suspicion.

Arabic numbers were even banned in the city of Florence in 1299 on the grounds

that “they were easier to falsify than Roman numerals”.

Thanks to his father’s job, Fibonacci had the opportunity to meet the great

mathematicians that were outside the Eastern bubble (Egypt, Syria, Algeria,

Greece, etc.) during long journeys through different countries in the Arabic

world and the Mediterranean.

He later returned to Italy, and when he was 32, he published the book Liber abaci (1202), which explained the importance of the Arabic numbering systems

and he applied it to different everyday situations in the trade world to prove that

it was more practical than the Roman numeral system: foreign exchange,

commercial accounting, converting weights and measurements, etc.

A quarter of a century later (1227), he published a second edition of the

same book, extended and rewritten, that has become the reference version

of “Liber abaci”, as there are no copies of the first handwritten edition from 1202.

mathematicians that were outside the Eastern bubble (Egypt, Syria, Algeria,

Greece, etc.) during long journeys through different countries in the Arabic

world and the Mediterranean.

He later returned to Italy, and when he was 32, he published the book Liber abaci (1202), which explained the importance of the Arabic numbering systems

and he applied it to different everyday situations in the trade world to prove that

it was more practical than the Roman numeral system: foreign exchange,

commercial accounting, converting weights and measurements, etc.

A quarter of a century later (1227), he published a second edition of the

same book, extended and rewritten, that has become the reference version

of “Liber abaci”, as there are no copies of the first handwritten edition from 1202.

Federico II de Hohenstaufen (1194-1250) was the Holy Roman Emperor when

he learned about the work of Fibonacci thanks to the correspondence that the mathematician maintained after returning to Italy with certain members of his court, including Michael Scotus, an astrology admired by the Pisan and to whom

he dedicated the second edition of his most famous book.

Johannes of Palermo also formed part of the Court and challenged Fibonacci

with a mathematical problem that would give him a place in history forever.

The rabbits problem

he learned about the work of Fibonacci thanks to the correspondence that the mathematician maintained after returning to Italy with certain members of his court, including Michael Scotus, an astrology admired by the Pisan and to whom

he dedicated the second edition of his most famous book.

Johannes of Palermo also formed part of the Court and challenged Fibonacci

with a mathematical problem that would give him a place in history forever.

The rabbits problem

How many pairs of rabbits can be produced from this pair in one year,

if every month each pair breeds a new pair which reproduce after the second month?

Fibonacci accepted the challenge and resolved the problem, publishing the

He developed a numeric series that will be passed down throughout history as

the Fibonacci series. This succession of numbers starts with 0 and 1, and from

there on, each element or Fibonacci number is the sum of the previous two.

And that’s how Leonardo represented the reproductive problem of the rabbits which, although it is an artificial model in the case of these animals (since biologically

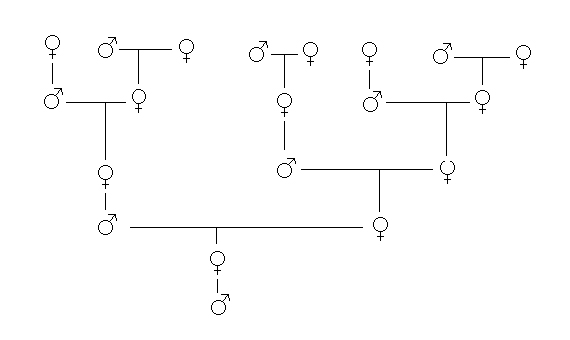

Only the queen reproduces in a beehive: she’s the only one that lays eggs.

*If they are fertilized, worker bees are born (females).

With 50% of the genetics provided by the mother (the queen)

and the other 50 by the father (the drone).

*The drones or male bees are produced from unfertilized eggs.

Therefore, female worker bees have two parents and drones have one.

100% of their genetic information is provided by the mother.

Schema simulating the genealogical tree of bees / Image: Canada’s SchoolNet

Bees are not the only exception, and these numbers are behind many

different phenomenon of nature: the arrangement of flower petals,

the formation of hurricanes, etc. How is this possible?

Are they a magical combination, the “abracadabra” of mathematics?

The mystery behind this succession of numbers that seems to be written in the mathematical foundations that surround us (at least in many of things that

exist around us) have fascinated experts from many fields of science for centuries,

and there are even publications specialized in finding new fields related with it.

different phenomenon of nature: the arrangement of flower petals,

the formation of hurricanes, etc. How is this possible?

Are they a magical combination, the “abracadabra” of mathematics?

The mystery behind this succession of numbers that seems to be written in the mathematical foundations that surround us (at least in many of things that

exist around us) have fascinated experts from many fields of science for centuries,

and there are even publications specialized in finding new fields related with it.

From medieval mathematics to the “divine proportion”

But how much “magic” is there in the famous Fibonacci series?

To what point was the Pisan the exclusive discoverer of these

numbers and the proportions that give rise to the relationship between them?

History has left clues about previous references to the formula, as is the case

of various Indian mathematicians: Gopala (1135) and Hemachandra (1150),

who had already mentioned it in their documents several decades before Fibonacci

was born. Even several centuries later, Kepler (1571-1630) continued to be

fascinated with the research into this series and, centuries later, developed the

concept that would go down in history as “the divine proportion” in his book

“Strena Seu de Nive Sexangula” (1611).

To what point was the Pisan the exclusive discoverer of these

numbers and the proportions that give rise to the relationship between them?

History has left clues about previous references to the formula, as is the case

of various Indian mathematicians: Gopala (1135) and Hemachandra (1150),

who had already mentioned it in their documents several decades before Fibonacci

was born. Even several centuries later, Kepler (1571-1630) continued to be

fascinated with the research into this series and, centuries later, developed the

concept that would go down in history as “the divine proportion” in his book

“Strena Seu de Nive Sexangula” (1611).

Kepler rediscovered the sequence using the proportion that existed between

the consecutive terms in the series. 2 is to 3 what 3 is to 5 and what 5 is to 8 and

so on with all the elements. Therefore, there is a proportion (divine proportion or

golden ratio) which is constantly maintained when dividing any of the numbers by

their predecessor in the series. This proportion is represented by the number phi

(in honor of the Greek sculptor Fidias, and not Fibonacci): φ = 1.618.

the consecutive terms in the series. 2 is to 3 what 3 is to 5 and what 5 is to 8 and

so on with all the elements. Therefore, there is a proportion (divine proportion or

golden ratio) which is constantly maintained when dividing any of the numbers by

their predecessor in the series. This proportion is represented by the number phi

(in honor of the Greek sculptor Fidias, and not Fibonacci): φ = 1.618.

In his book “Strena Seu de Nive Sexangula” (1611), Kepler defined the importance

of this proportion which, according to him, developed in a similar way in the

reproductive process, which managed to perpetuate him.

Kepler’s idea about a biological auto-replication process marked by the Fibonacci sequence was ignored by biologists until not long ago, when Phyllotaxis -the

arrangement of leaves on a stalk- was scientifically consolidated.

of this proportion which, according to him, developed in a similar way in the

reproductive process, which managed to perpetuate him.

Kepler’s idea about a biological auto-replication process marked by the Fibonacci sequence was ignored by biologists until not long ago, when Phyllotaxis -the

arrangement of leaves on a stalk- was scientifically consolidated.

Statue of Fibonacci in the cemetery of the city of Pisa (Italy)

/ Image: courtesy of Holoweb.

/ Image: courtesy of Holoweb.

However it came about, the discovery of the numerical series that gave rise

to divine proportion was enough to give Fibonacci immortality in time and

in the memory of mathematicians. In the 19th century, a statue was

erected in his honor in Pisa, which can be visited today in the city’s cemetery,

in the Piazza dei Miracoli.

There isn’t much information about the end of his life, although there is

a decree by which the Republic of Pisa granted Leonardo a lifetime salary

in 1240 in recognition of his service to the city as an accounting advisor.

Dory Gascueña for OpenMind

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου