Unlike the Pantheon … virtually all the concrete structures one sees today

will eventually need to be replaced,” writes Robert Courland is his weighty tome Concrete Planet, “costing us trillions of dollars in the process.”

While there is some debate over when and where the first concrete was

used – the Göbekli Tepe temple in modern-day Turkey was built using

T-shaped pillars of carved limestone approximately 12,000 years ago,

desert traders used early concrete to make underground water cisterns

8,000 years ago, and the ancient Egyptians used gypsum and lime to

make mortars – there is little dispute that the first people to use concrete

in the way we do today were the Romans.

The Romans used it in everything from bath houses to harbours,

aqueducts to the Colosseum, systematising its production and application

from the third century BC to the fall of the empire in the fifth century AD.

Unlike modern reinforced concrete – which can last about a hundred years without major repairs or replacement – many Roman concrete structures

are still with us many centuries later.

The Göbekli Tepe temple (left) and the step pyramid of Djoser, Egypt.

Photographs: Getty Images/Mohamed El-Shahed/AFP

will eventually need to be replaced,” writes Robert Courland is his weighty tome Concrete Planet, “costing us trillions of dollars in the process.”

While there is some debate over when and where the first concrete was

used – the Göbekli Tepe temple in modern-day Turkey was built using

T-shaped pillars of carved limestone approximately 12,000 years ago,

desert traders used early concrete to make underground water cisterns

8,000 years ago, and the ancient Egyptians used gypsum and lime to

make mortars – there is little dispute that the first people to use concrete

in the way we do today were the Romans.

The Romans used it in everything from bath houses to harbours,

aqueducts to the Colosseum, systematising its production and application

from the third century BC to the fall of the empire in the fifth century AD.

Unlike modern reinforced concrete – which can last about a hundred years without major repairs or replacement – many Roman concrete structures

are still with us many centuries later.

The Göbekli Tepe temple (left) and the step pyramid of Djoser, Egypt.

Photographs: Getty Images/Mohamed El-Shahed/AFP

The key to its longevity appears to be the use of volcanic ash, or pozzolana. Where modern concrete is a mix of lime-based cement, water, sand and an aggregate such as gravel, the recipe for concrete set down by architect

Vitruvius in the first century BC involved pozzolana and chunks of volcanic

rock, known as tuff. When it comes to Roman marine concrete, used to construct piers and breakwaters, research published in 2017 found that

the addition of sea water actually strengthened these structures over time,

making them harder and harder over the millennia.

The most striking surviving example of Roman concrete is the Pantheon, which the painter Michelangelo described as an “angelic and not human design”. It still looks strikingly modern today and it remains the largest non-reinforced concrete dome in the world, 19 centuries after it was built.

Sunlight illuminates a detail of the Pantheon’s concrete dome.

Photograph: AndySmyTravel/Alamy

Rediscovered after 1,400 years

With only a couple of isolated exceptions, around 1,400 years passed after

the fall of the western Roman empire until concrete was used again on any great scale.

The invention of reinforced concrete gave the material a new life. It was pioneered in France in the mid-19th century, but was popularised by

California-based engineer Ernest Ransome, who poured over iron (and later steel) bars to improving its tensile strength.

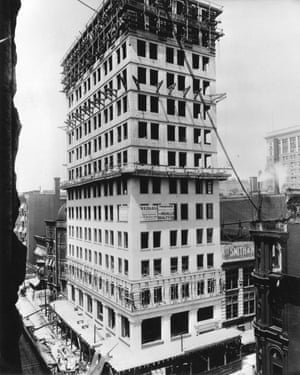

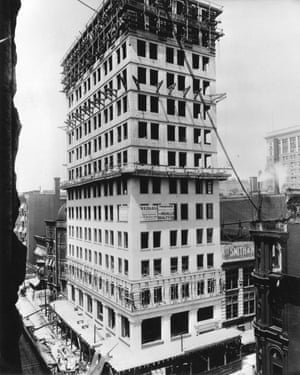

The first reinforced concrete skyscraper, the 1903 Ingalls Building in Cincinnati;

underneath the first reinforced concrete bridge, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco.

Photographs: Cincinnati Museum Center/Getty Images

Thomas Edison stands by a model of his prototype all-concrete house in 1910.

It proved too complicated to build, and he was forced to settle for a simpler design.

Photograph: National Building Museum/AP

“I am going to live to see the day when a working man’s house can be built

of concrete in a week,” said Edison.

“If I succeed, it will take from the city slums everybody who is worth taking.”

To that end, the inventor announced he would give away his patented technology to anyone who promised to reserve the majority of new homes

for working class residents and make no more than 10% profit – but it took another decade before the first were built.

A few concrete house projects were launched across the US – including

what became known as Cement City in in Donora, south of Pittsburgh – but the dream of cheap, roomy concrete houses never really took off.

It took architect Frank Lloyd Wright to realise the potential of reinforced concrete to create completely new forms.

His first concrete building – the 1908 Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois – is widely considered the world’s first modern building. He used the material in many of his designs, including perhaps his most famous work – Fallingwater

in Mill Run, Pennsylvania – whose hanging cantilevers project out over the stream’s small waterfall in a way which would have been impossible without

the tensile strength of reinforced concrete.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater house in Mill Run,

Pennsylvania, was completed in 1939.

Photograph: Corbis/Getty

Niemeyer’s 1950 Ibirapuera Park Auditorium in São Paulo;

Niemeyer’s 1950 Ibirapuera Park Auditorium in São Paulo;

Lloyd Wright’s Solomon R Guggenheim museum under construction

in Manhattan in the 1950s; the interior of Eero Saarinen’s 1960s TWA terminal.

Photographs: SambaPhoto/Iata Cannabrava/Getty/Charles Phelps Cushing/Bettmann Archive

Of course, alongside the beautiful forms dreamt up by talents such as Niemeyer and Lloyd Wright, modern concrete is also the preferred material

for soul-destroying office blocks and drab multi-storey car parks. Its hulking grey blocks are ubiquitous – to be found throughout every nation and city

on earth.

Despite growing environmental concerns, concrete remains the material

of choice for most builders, with 3D printing technologies offering it

new life: think Shanghai’s 3D printed bridge unveiled earlier this year,

the US military’s plans to 3D-print troop barracks, and plans in Eindhoven

in the Netherlands to build the world’s first habitable 3D-printed concrete houses.

The world’s first commercial housing project based on 3D-concrete

printing is to be built in Eindhoven.

Photograph: 3DPrintedHouse

But none of these modern structures are going to outlast the Pantheon

– least of all any which include concrete reinforced with steel bars.

“Rebar made the modern world possible,” writes Courland, “but in terms

of longevity, reinforced concrete is no match for what the Romans used.

Over decades [rebar] rusts … and will expand enough to put cracks in

the concrete. The impressive tensile strength of many of our structures

is only temporary.”

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/feb/25/a-brief-history-of-concrete-

from-10000bc-to-3d-printed-houses?CMP=share_btn_fb&fbclid=IwAR0flJU13

V4YSjHnGUOruzJVi-JeqxNH6hPQZCrxLFEq8_pHS0fhUwFCuv0

Vitruvius in the first century BC involved pozzolana and chunks of volcanic

rock, known as tuff. When it comes to Roman marine concrete, used to construct piers and breakwaters, research published in 2017 found that

the addition of sea water actually strengthened these structures over time,

making them harder and harder over the millennia.

The most striking surviving example of Roman concrete is the Pantheon, which the painter Michelangelo described as an “angelic and not human design”. It still looks strikingly modern today and it remains the largest non-reinforced concrete dome in the world, 19 centuries after it was built.

Sunlight illuminates a detail of the Pantheon’s concrete dome.

Photograph: AndySmyTravel/Alamy

Rediscovered after 1,400 years

With only a couple of isolated exceptions, around 1,400 years passed after

the fall of the western Roman empire until concrete was used again on any great scale.

The invention of reinforced concrete gave the material a new life. It was pioneered in France in the mid-19th century, but was popularised by

California-based engineer Ernest Ransome, who poured over iron (and later steel) bars to improving its tensile strength.

Ransome’s first rebar concrete building was the Arctic Oil Company Works warehouse in San Francisco, which was completed in 1884. Five years later Ransome built the Alvord Lake Bridge in Golden Gate Park – the world’s first reinforced concrete bridge. The warehouse was demolished in 1930 but the bridge remains the world’s oldest surviving reinforced concrete structure.

Ransome himself was not involved in the construction of the world’s first concrete skyscraper, the 16-storey Ingalls Building in Cincinnati in 1903,

but it would not have been possible without his rebar(reinforcing bar)method.

Ransome himself was not involved in the construction of the world’s first concrete skyscraper, the 16-storey Ingalls Building in Cincinnati in 1903,

but it would not have been possible without his rebar(reinforcing bar)method.

The first reinforced concrete skyscraper, the 1903 Ingalls Building in Cincinnati;

underneath the first reinforced concrete bridge, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco.

Photographs: Cincinnati Museum Center/Getty Images

Meanwhile, American inventor George Bartholomew had constructed the

world’s first concrete street in Bellefontaine, Ohio.

Concrete lasts well compared with asphalt roads, which are made using bitumen, and it was widely used throughout the US interstate highway

system. The original 1891 Bellefontaine concrete street is still there today.

In late summer 1906, not long after the devastating San Francisco earthquake, Thomas Edison announced his proposal to mass-produce

concrete houses which would be resistant to fire and tremors, and immune

to termites, mildew and rot. Houses had been custom-built from reinforced concrete for several decades but they were expensive. Edison’s plan for construction on an industrial scale would drive down prices.

Residents would be able to sit on Edison-designed cast-concrete furniture,

keep food fresh in his concrete fridge and be entertained by his concrete phonograph cabinet.

world’s first concrete street in Bellefontaine, Ohio.

Concrete lasts well compared with asphalt roads, which are made using bitumen, and it was widely used throughout the US interstate highway

system. The original 1891 Bellefontaine concrete street is still there today.

In late summer 1906, not long after the devastating San Francisco earthquake, Thomas Edison announced his proposal to mass-produce

concrete houses which would be resistant to fire and tremors, and immune

to termites, mildew and rot. Houses had been custom-built from reinforced concrete for several decades but they were expensive. Edison’s plan for construction on an industrial scale would drive down prices.

Residents would be able to sit on Edison-designed cast-concrete furniture,

keep food fresh in his concrete fridge and be entertained by his concrete phonograph cabinet.

Thomas Edison stands by a model of his prototype all-concrete house in 1910.

It proved too complicated to build, and he was forced to settle for a simpler design.

Photograph: National Building Museum/AP

“I am going to live to see the day when a working man’s house can be built

of concrete in a week,” said Edison.

“If I succeed, it will take from the city slums everybody who is worth taking.”

To that end, the inventor announced he would give away his patented technology to anyone who promised to reserve the majority of new homes

for working class residents and make no more than 10% profit – but it took another decade before the first were built.

A few concrete house projects were launched across the US – including

what became known as Cement City in in Donora, south of Pittsburgh – but the dream of cheap, roomy concrete houses never really took off.

It took architect Frank Lloyd Wright to realise the potential of reinforced concrete to create completely new forms.

His first concrete building – the 1908 Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois – is widely considered the world’s first modern building. He used the material in many of his designs, including perhaps his most famous work – Fallingwater

in Mill Run, Pennsylvania – whose hanging cantilevers project out over the stream’s small waterfall in a way which would have been impossible without

the tensile strength of reinforced concrete.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater house in Mill Run,

Pennsylvania, was completed in 1939.

Photograph: Corbis/Getty

The 1930s also saw the construction of the Hoover Dam on the Colorado

River near Las Vegas. At the time the dam was comfortably the largest

concrete project ever completed, using more than 3m cubic metres of the material, although it was soon outweighed by the Grand Coulee Dam (pdf)

on the Columbia River (and both have since been dwarfed by China’s 27m

cubic metre Three Gorges Dam).

Through the 1950s, visionary architects shaped concrete into ever more exotic and adventurous forms. “There is no reason to design buildings that

are more basic and rectilinear,” said one of the material’s greatest pioneers, Oscar Niemeyer, “because with concrete you can cover almost any space.”

River near Las Vegas. At the time the dam was comfortably the largest

concrete project ever completed, using more than 3m cubic metres of the material, although it was soon outweighed by the Grand Coulee Dam (pdf)

on the Columbia River (and both have since been dwarfed by China’s 27m

cubic metre Three Gorges Dam).

Through the 1950s, visionary architects shaped concrete into ever more exotic and adventurous forms. “There is no reason to design buildings that

are more basic and rectilinear,” said one of the material’s greatest pioneers, Oscar Niemeyer, “because with concrete you can cover almost any space.”

Lloyd Wright’s Solomon R Guggenheim museum under construction

in Manhattan in the 1950s; the interior of Eero Saarinen’s 1960s TWA terminal.

Photographs: SambaPhoto/Iata Cannabrava/Getty/Charles Phelps Cushing/Bettmann Archive

Of course, alongside the beautiful forms dreamt up by talents such as Niemeyer and Lloyd Wright, modern concrete is also the preferred material

for soul-destroying office blocks and drab multi-storey car parks. Its hulking grey blocks are ubiquitous – to be found throughout every nation and city

on earth.

Despite growing environmental concerns, concrete remains the material

of choice for most builders, with 3D printing technologies offering it

new life: think Shanghai’s 3D printed bridge unveiled earlier this year,

the US military’s plans to 3D-print troop barracks, and plans in Eindhoven

in the Netherlands to build the world’s first habitable 3D-printed concrete houses.

The world’s first commercial housing project based on 3D-concrete

printing is to be built in Eindhoven.

Photograph: 3DPrintedHouse

But none of these modern structures are going to outlast the Pantheon

– least of all any which include concrete reinforced with steel bars.

“Rebar made the modern world possible,” writes Courland, “but in terms

of longevity, reinforced concrete is no match for what the Romans used.

Over decades [rebar] rusts … and will expand enough to put cracks in

the concrete. The impressive tensile strength of many of our structures

is only temporary.”

from-10000bc-to-3d-printed-houses?CMP=share_btn_fb&fbclid=IwAR0flJU13

V4YSjHnGUOruzJVi-JeqxNH6hPQZCrxLFEq8_pHS0fhUwFCuv0

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου